A series of civic dialogues have been taking place in Oakland on the subject of development and gentrification. Oakland Reconstructed: The Birth of a District was one such event, billing itself as an attempt to “bring as many un-likeminded people as possible together to have as honest a discussion as participants were willing to engage [in].” PopFront will be covering this and future forums in Oakland as they progress.

As the tech boom creeps north and east, it seems inevitable that Oakland will face the same structural changes that remade San José, the Peninsula and now San Francisco. But is redevelopment inherently harmful? On April 2nd, a town-hall style forum was held in midtown Oakland to tackle this very topic. The group that hosted the event, Top Ten Social Club, titled the evening “Oakland Reconstructed.” The panel featured Jahmese Myres, a local Senior Research Associate at the East Bay Alliance for a Sustainable Economy (EBASE); Jeremy Liu, a Bay Area native and Co-Founder of Creative Development Partners (CDP); Orson Aguilar, Executive director at the local Greenling Institute; Alan Dones, an Oakland Native and principal of ADCo, LLC and managing partner and co-founder of SUDA, LLC; and Mike Ghielmetti, a local founder and president of Signature Development Group.

Oakland Reconstructed billed itself as an town hall-style attempt to bring diverse, opposing voices together to find common ground in the debates over development. Held at the Impact Hub, a casual-chic coworking space, the swelling number of attendees reflected the pride and engagement for which Oakland residents are known. The concept: to open a dialogue about how Oakland can deviate from the traditional pattern of gentrification—displacement and eviction along racial and class lines—and remain one of the last historic African American cities in the Bay Area, let alone America.

Fittingly, Oakland Reconstructed took place in the heart of the Broadway Corridor, an area of downtown that is slated for massive development. The projected scope of the Broadway Corridor redevelopment runs in a 3.25 mile span that stretches from Jack London Square to the Oakland Hills. If Citigroup, developers, and city planners realize their joint vision, the Broadway Corridor will get a multi-million dollar facelift. Unsurprisingly, much of the money for the redevelopment of the Broadway Corridor originates from big banks, inspiring fears of a Goldman Sachs-style civic disaster. This kind of large-scale development is potentially a positive step for Oakland; yet with the unemployment rate for Oakland’s lowest income residents at roughly 30%, it is hard to know if Oakland’s underemployed poor stand to be hired. According to the CEO of the Oakland Business Development Corporation, the redevelopment will bring jobs to low-wage workers; but it is unclear if their wages will be enough to keep them in Oakland.

It was evident from the crowd’s comments that no one thought letting financial giants like Citigroup decide the fate of Oakland constituted progressive change; indeed, no community wants to be at the mercy of paternalistic financiers pushing their so-called solutions. There was a palpable fear in the crowd that the redevelopment would inaugurate a San Francisco-style gentrification trend that has already pushed poverty toward the suburbs. According to a UC Berkeley study, the poverty rate in Bay Area suburbs has gone up 16% since 2000, and the overwhelming majority of the poor are Black and Latino. The staggering decline of the African American community in San Francisco is a reminder that change could mean a further shift and sense of destabilization for working people of color.

The host space Impact Hub, a for-profit European benefit corporation that operates co-working spaces across the planet, attracts a techie crowd that likely includes people who displace lower-income people of color. Yet it was clear from the crowd’s questions and comments that there were many lower-income attendees, too—illustrating a commitment to inclusivity. This brought to light the complexity of redevelopment in Oakland: while displacement has been a factor for the African American community, Oakland has also experienced an influx of African American young professionals who are upwardly mobile, some of them homeowners. Property is a cornerstone to wealth, and like any other American, young African Americans should, and have, taken advantage of their skills and talents to achieve financial stability and create wealth. And who can fault them? This is the bedrock of the American dream, which should not be the white American Dream. With the realities of class and race in mind, the panel discussion began with the question:

Why is Oakland home for you?

As the panelists dove into their personal stories, it was clear that the love people have for the city of Oakland cannot be monetized. But the complex issue of how economic change effects the pre-existing community keep economics looming. Ms. Myres came to Oakland a few years ago to do social justice work; while Mr. Liu was a Bay Area native. It was striking to see affluent people of color talk like Orson Aguilar and Jahmese Myers talk about how they migrated to Oakland to be part of the rich community, adding their skill-sets and passions. The economic divide within racial communities is a complex, little-discussed issue in the gentrification dialogue. All panelists agreed on the need for what they called “inclusive gentrification” and development to help lower-income people rise out of poverty while remaining in Oakland.

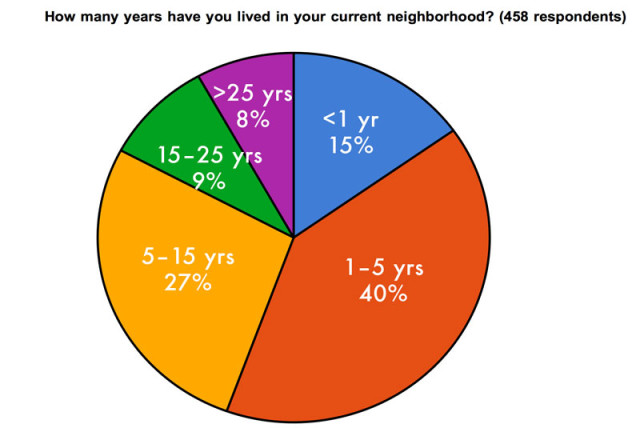

In a separate, informal, poll taken of the audience showed that 19% of people had lived in Oakland for 1-5 years, 26% 5-15 years, 15% 15-25 years, and 36% had lived in Oakland for more than 25 years. The recent transplants in the panel and the audience all commented that they moved to be a part of the Oakland community. They valued the political, gender, racial, sexual, and economic diversity of Oakland and wanted to improve upon the existing community, not destroy it. This is striking compared to the tech transplants of San Francisco, many of whom seem disinterested in civic engagement outside of tech bubbles. It was also clear that many attendees saw Oakland as home, not a temporary place they live right now—a distinction that makes Oakland transplants unique.

The call for inclusive redevelopment struck a chord with everyone in the room. The reality for many low income people (especially of color) in Oakland has been an exodus from the city. According to the same UC Berkeley study,

demographic shifts have been especially dramatic in historically Black cities [like] Oakland, whose Black population dropped by 23% from 2000 to 2010 as residents left for more affordable parts of the region – smaller cities in Contra Costa County like Antioch or farther away to Tracey or Stockton. These areas have seen a dramatic rise in their Black populations since 2000.

This dramatic, racially-tinted exodus does not bode well.

During World War II, Henry J. Kaiser recruited African American sharecroppers from the South to come to Oakland to work in the shipyards. In that period, Oakland was a place where the African American community came for economic opportunity. (Before World War Two, African Americans made up only 3% of the population). During the war, thousands of African Americans came from the South, along with poor white Southerners. This migration west was economically motivated, similar to the Dust Bowl migration a few decades prior. The South offered little beyond sharecropping for African Americans; the opportunity to be a longshoreman, in a place without Jim Crow, was appealing to many. Hence, since the 1940s the African American community was a staple of Oakland, despite the discrimination and economic exclusion they often faced.

Redlining, such as took place from the 1950s on, was a process of systematic economic exclusion. It was characterized by a literal drawing of a red line around African American and Latino communities, with banks and lenders committing not to cross that red line and invest in communities of color. Redlining resulted in lack of access to financing, healthcare, and even food. Property values in historically redlined neighborhoods were low until gentrification made traditionally Black communities desirable.

There is an inherent injustice in marginalizing a group, excluding them from opportunity, and then later valuing their physical communities through their removal. The crowd rejected the idea that Oakland is the next frontier of tech gentrification. A Mercury News statistic showed in 2012 that Blacks make up 2.5% of the tech industry, Latinos make up 4.2%, whites 40.7%, and Asians 50.1%. Seemingly, communities of color stand to lose when tech comes to town. Further, the infiltration of tech buses in historically black Oakland neighborhoods stokes fears that the East Bay is next to be annexed by wealthy techies.

The next question for Alan Dones and Mike Ghielmetti: What do you see for Oakland 2024? The answer was a mix of hope and fear.

HOPE

The city of San Francisco has recently seized the opportunity to attract some of the biggest companies in the world, hoping that their presence will bring economic viability and prestige. Yet numerous American municipalities have been underfunded and slowly bankrupted over the past 30 years by doing exactly what San Francisco has been doing: issuing tax breaks to corporations, forcing cities to compete with each other for tax breaks in a race to the bottom. This benefits corporations and their profit margins far more than the people, and strips cities their bargaining power. Ideally, the Oakland community needs to have a say in the future of their home: in order to buck the trend, the city is going to need a committed group of developers and city officials that are willing to go against the neoliberal grain.

In San Francisco, the tech industry has decimated the affordable housing market, one neighborhood at a time. The San Francisco city government’s spinelessness towards tech is a reminder that redevelopment could be brutal for Oakland residents. Yet no one knows exactly what kind of change is afoot. Must Oakland join the rank of cities unmade by tax breaks for corporations at the expense of working people? Will redevelopment result in more landlords converting properties into condos, invoking the Ellis Act? The hope expressed through Oakland Reconstructed was that avoiding more economic and civic destruction is possible.

FEAR

What if gentrified Oakland becomes a bourgeois wasteland of condos and high-end restaurants, like SoMa or the Marina? This fear was palpable at Oakland Reconstructed; there were calls for more city government accountability, and a restructuring of city tax money to invest in the local community and enhance preexisting cultural infrastructure, rather than destroy it.

On the question of what form reconstruction might take, Mr. Dones and Mr. Ghielmetti were asked the vague question: What does Oakland reaching its full potential look like? In their answer, they invoked the history of formerly African American neighborhoods like Brooklyn, where “full potential” meant an exodus of people of color, as well as lower-income people. The redevelopment of Brooklyn (along with other New York neighborhoods like Harlem) pushed out the African American community, and resulted in many Blacks moving back to the South. Indeed, according to the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, 17% of African Americans who moved to the South in the past decade came from New York. This shift has put more African Americans in poverty in states with little economic opportunity. The prospect of a massive remigration from the Bay Area would signal a giant step backward for a community whose grandparents and great-grandparents came from the South to Oakland in search of economic opportunity.

Panelist Mr. Dones also commented on the failure of below-market rate units to solve the issue of displacement. Below-market-rate units were conceived of as a solution to this problem—the goal of them being to adequately provide for the people pushed out during new development, as market rate is frequently unaffordable for the majority of working people. The panelists were then asked: if redevelopment changes the housing market, who will be economically shut out? The fear in the room was that the spillover from the spiraling San Francisco rental market would make Oakland market rate mean tech rate. Oakland now stands to see construction breaking ground all over the city, and the redevelopment of Oakland is seen by city officials and developers as a positive economy step for the city. However, depending on what one’s economic position is, the bettering of Oakland may mean being shut out economically and forced to move north, east, or be homeless.

Witnessing the enthusiasm and engagement of the Oakland community, it’s clear that no solution can be found in two hours. Yet what is happening is a good start. There was a communitarian spirit embodied by the attendees’ civic pride and cultural commitment to inclusivity and social justice; this gives life to the idea that Oakland could be a prototype for sustainable and inclusive redevelopment.

With the mayoral race approaching in November, development and gentrification will be at the forefront of voters’ minds. As the elections get closer, PopFront will be following a series of civic dialogues this summer called Inclusive Oakland 2024.

“Fear of a Hipster Planet”