In considering the political firestorm in Venezuela, it may be best to start with a quantitative measure of populist will: elections. The government of Hugo Chávez—and the associated Bolivarian Revolution, more movement than literal revolution—came to be in 1999, following the elections of 1998 in which Chávez won a majority, 56%, of the national vote. In second place came the center-right candidate, Salas Römer, with 40% of the vote. Chávez’s margin of victory was particularly impressive given Venezuela’s abundance of political parties.

After less than a year of governance, the Chávez administration called a public referendum to approve the creation of a Constitutional Assembly, which would be charged with the task of drafting a new constitution to replace the outdated and outstanding one written 39 years prior by rural and business elites, and engineered to preserve their interests. The referendum passed with an unprecedented 88% of the vote.

To understand the near-universal public support for the 1999 constitutional referendum, one must go back to the prior constitution and the power struggle that led to its creation. The Constitution of 1961 was the result of the Punto Fijo pact, an informal agreement by the leaders of the two dominant political parties of Venezuela: Copei, a party that represented the free market interests of landed and agrarian, traditional oligarchical elites, and Acción Democrática (AD), which was largely the political vehicle for urban industrialists (new money that had economic interests in protectionist trade policies). Punto Fijo was an agreement between these two similar parties to essentially share power in the face of radical left-wing opposition. (To be precise, a third party, the Unión Republicana Democrática (URD) also signed the Pacto Punto Fijo but withdrew shortly after.)

The Punto Fijo pact was created out of fear. Latin American Marxism, left-wing armed insurrectionary groups and newfound leftist threats at the ballot box terrified the two parties of oligarchy. Punto Fijo was the result of these two, formerly competing elite sectors realizing that without a constitutional reform, their power would be usurped by leftist/populist opposition and the party would be over for both. Any squabble between the two oligarchical parties paled in comparison to the real threat of a common-Cuban style enemy; indeed, the Cuban revolution helped push the land-holding and business oligarchs of Venezuela toward the bargaining table.

The pact created what was essentially a single-party state within the pretext of democracy; while in theory either party could win the executive and legislative branches, Punto Fijo established that the ruling party would fill its ministerial, diplomatic and other positions with high-ranking members of the other party. Likewise the 1961 constitution dictated that municipal and provincial bodies would be centrally appointed, rather than voted in through municipal elections. This was a perk for business and land-holding stakeholders, but a blow to the majority of Venezuelans, who lost political agency due to the virtual single-party state that the pact created.

So it is in this context that we should consider the rise of Chavismo. In fairness, the movement did attempt to take power via nondemocratic means in 1992. But there is ample evidence that in place of a very hollow democracy based on the economic interests of a small portion of Venezuelan society—with institutional rules that mirrored these interests and ensured their prosperity—the attempted coup of 1992 was aimed at installing a profound and meaningful democracy, one that would be more direct and represent the Venezuelan populace as a whole. The new constitution implemented in December of 1999, which was drafted by the democratically-elected Constitutional Assembly, was then supported by 72% of the Venezuelan people. The electoral results show that the vast majority of Venezuelans wanted a new democratic institutional apparatus; international media’s dismissal of that majority is irresponsible and shortsighted.

* * *

Along with the international media, a dispiriting number of academics tend to dwell on the Bolivarian Revolution’s lack of respect for the “rule of law.” This sad fact seems to stem from either a limited America/Eurocentric understanding of constitutionality, or else a concerted attempt to misconstrue the historic realities of the Venezuelan people. The “rule of law” is not de facto “just” nor “democratic”; to champion “rule of law” as sacrosanct upholds a tradition of oppression and posits any change to oligarchical power as an unacceptably radical threat to said law. Ideally, law is the manifestation of the will of the people; in the case of Venezuela, this meant creating a constitution that represented the country as a whole.

The new, Chávez-era constitution was created only after massive democratic input. Compare the constitution of 1999 with that of 1961: when the political pact of AD and Copei rewrote the constitution in 1961, it was approved by a legislature already controlled by those who wrote it. Under the Chávez government every step of instituting a new constitution was always approved by direct democracy, by national referendum, and written by a body that was created solely, directly and democratically, to draft it.

Constitutions are fundamental to the framework of the state. But they evolve, and are not timeless. Insofar that they are inherently based on specific ideologies that change with time and economic interest, there is no reason that constitutions should not be changed in a democratic way. The United States is the exception rather than the rule when it comes to constitutional change: we are stuck with antiquities like the Electoral College, or a large gray-area when it comes to protecting privacy (the Founding Fathers evidently did not anticipate the Internet). The current Constitution of Venezuela is the twenty-seventh iteration for a nation younger than the United States. The historical precedent of Venezuela was that of an ever-changing constitutional structure; to say the hyper-democratic constitutional reform of 1999 defied the “rule of law” is meretricious.

Time and time again, the electoral process has legitimized and underpinned all formal political developments. The Venezuelan independent body entrusted with conducting elections, the National Electoral Body of Venezuela, has been praised over and over by international organizations for its independence, impartialness and quality.

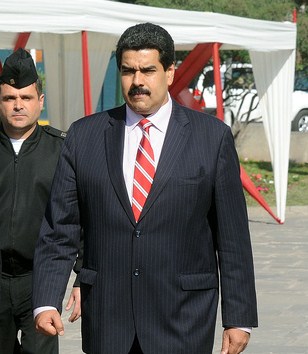

In 2013, Nicolás Maduro assumed powers of the presidency after a special election, winning by a slight 1.5% margin. This tiny margin—presaging a growing polarization in Venezuelan society—is the key to understanding the current crisis of Venezuelan democracy and the rise of actors intent on destabilizing the nation, which not only include national right-wing elements but also the increased role of the US.

The leader of the democratic opposition, Henrique Caprildes Radonski, continues to underperform electorally. After facing electoral disappointment at provincial and federal levels, the opposition turned from an electoral strategy to one based on extralegal methods, abandoning the ballot box and turning to agitation, chaos and the prospect of a civil war as a way to destabilize the progressive momentum of the last 15 years.

Part II, “Different Class, Different Interests,” will run on Saturday, 3/8.

Awesome content! This article walks a person who doesn’t know much about the Venezuela unrest, like myself, through the history of what brought the situation to where it is. I’m a little upset about the cliff hanger but I look forward to read the next installment on Saturday.